Understanding the rental sector

19th July 2017

Irish homeowners continue to reduce mortgage debt levels

19th July 2017The challenge of housing obsolescence

Dublin Institute of Technology’s Lorcan Sirr believes that the Government does not have an accurate register of all the domestic dwellings that currently exist in Ireland.

“Analysis of the 2016 preliminary census results showed anomalies between the level of housing that was built and the actual number of houses added to overall stock levels,” he says.

“Between 2011 and 2016, a total of 50,591 houses were constructed in the Republic of Ireland. Yet, our official national housing stock figures only rose by a figure of 18,891. This confirms that these numbers exist in a twilight zone.”

Sirr highlights the issue of obsolescence as one that is impacting on these national statistics. He defined an obsolescent dwelling as one that is uninhabitable and unused.

According to Sirr’s figures, a total of 123 houses become obsolete in Ireland every week, or 6,394 houses a year. The difference between the headline figure of nearly 51,000 houses being built in Ireland annually and the actual net gain of just short of 19,000 is due to obsolescence.

“This reality must be factored into the overall housing demand equation,” he says.

Sirr points out that obsolescence can occur for a number of reasons. These include: neglect, fecklessness, financial constraints, too much money to care, regulation changes, family disputes and lack of awareness. This latter point is particularly attributable to properties with overseas owners.

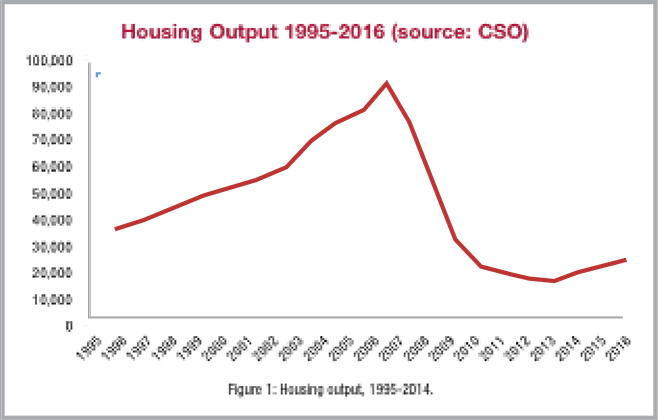

According to Sirr, the impact of obsolescence becomes more critical as the numbers of annual completions decrease.

“In other words, obsolescence is relatively constant at 4 per cent to 6 per cent per annum, whereas the number of annual completions fluctuates,” he says.

“Obsolescence is affecting government housing policy at two levels. In the first instance it is acting to reduce the actual number of houses available, which is impacting on future build targets.

“However, it is also hindering government’s desired aim of ensuring that best use is made of the housing stock that already exists in the country.

“Pillar five of the Rebuilding Ireland programme is dedicated to this specific challenge. Its core objective is to ensure that existing housing stock is used to the maximum degree possible, focussing on new measures to use vacant facilities, so as to renew rural and urban areas.

“This cannot be achieved until a better grip is secured on the obsolescence problem.”

Sirr challenges the accuracy of the new build figures reported in Ireland.

“The current practice of using ESB’s new connection figures is not fit for purpose,” he stresses.

“A house completion is not necessarily a new house: a house completion is measured by a new connection to the ESB grid. This could, therefore, include houses that had been built years ago but never connected, or temporary connections during construction works, or the conversion of a garage to a ‘granny flat’.

“There is estimated to be a 20 per cent margin of error in house completion statistics by using this method of measurement.”

He continues: “These issues serve only to highlight the importance of effectively managing our existing stock of houses, as well as increasing the supply of new builds.

“The distortion in the official housing figures, created by obsolescence and new build registrations must be sorted out.

“Fundamentally, we don’t really know the causes of obsolescence. This must change. There are economic implications regarding the inaccurate assimilation of housing data. Economic resources can be easily wasted in such circumstances. Poor investment in infrastructure can also follow, leading to a further drain on the public purse.

“Ireland’s housing stock is worth approximately €460 billion. This is a very large sum of money but it’s hard to manage what you can’t measure!”

Sirr says that the impact of obsolescence highlights the reality that resolving the current housing crisis involves the management of Ireland’s existing stock, as much as building new homes.

“Obsolescence needs to be a factor in housing statistical calculations and as part of housing policy,” he says.

“We require a better way of measuring our housing output. We know more about our farm animals: where they were born, what drugs they received, where they were slaughtered etcetera than we do about our housing stock.”

”We require a better way of measuring our housing output. We know more about our farm animals: where they were born, what drugs they received, where they were slaughtered etcetera, than we do about our housing stock.

“A State response to the housing crisis, therefore, should be 50 per cent about the construction of new housing and 50 per cent about better managing the stock we already have.

“New construction is a three to 10 year project but managing better the stock we have could start tomorrow.”

Sirr admits that the ownership of land is a sensitive topic, not just in Ireland.

“Many events of social significance and, indeed, social upheaval have had property and the ownership of property at their root. Much power, both collective and individual, such as the right to vote, has also derived from the ownership of property,” he says.

“To manage property better, it may well be necessary to challenge certain assumptions about the rights and obligations of ownership.

“It’s difficult for the State to manage housing better when everybody wants to control their own stock. However, it’s even more difficult for the State to manage housing better if some form of control isn’t taken.

“This means that the State may have to ask some questions about ownership, and about itself, and how far it is willing to go in order to balance individual ownership rights and national housing management needs.”

Sirr says that the Irish courts have shown that they are willing to go further than politicians on issues of property, ownership and their inherent rights.

“Politicians have been far weaker on issues of ownership, a good example of which is the vacant site levy, which was set at 3 per cent of the land’s value. This is a figure that will challenge no landowner when land values are rising by more than this amount each year.”

He adds: “Managing our existing housing stock better is a key factor in resolving the current housing crisis, and one that could have an immediate impact. To do that, however, we need a better grasp on what our stock is and how it is changing each year.

“Better management may also involve some tough political initiatives in order to encourage owners to use their property and land more productively. The notion of ownership itself, and what it means in Ireland, should also be examined.”

Sirr points out that the main driver of demand for housing is the headship rate. This is essentially the number of households that are forming. Factors such as people staying single for longer, family breakup and holiday homes all drive demand for housing.

“The State has little control over these factors,” he says. “However, obsolescence represents the second largest driver, where housing demand is concerned and this is an issue which the State can have a large degree of control over.”