Ó Cualann’s co-operative vision

19th July 2017

Understanding the rental sector

19th July 2017Dublin has a dysfunctional housing market

The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) has recommended the introduction of a Developers’ Tax to free up sites for building in areas of key demand such as Dublin.

The release of the National Asset Management Agency’s (NAMA) Annual Report for 2016 outlined that that the organisation had helped deliver 2,300 homes for social housing by the end of 2016 and invested €300 million in the repair and purchase of homes, which have been leased or sold to approved housing bodies and local authorities. It also stated that the number of unfinished housing estates had been reduced from 332 in 2010 to 11 as at the end of March 2017.

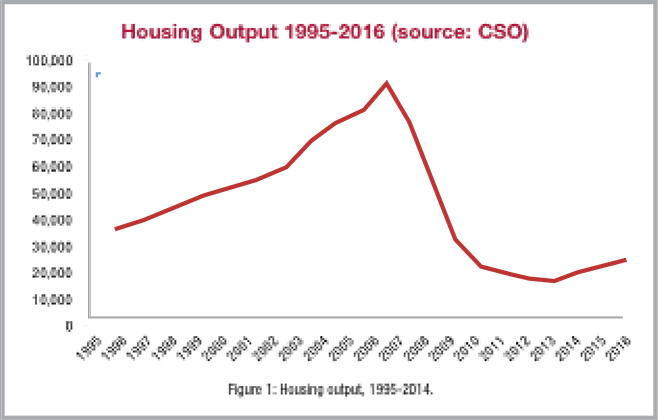

The level of social housing creation in falls well short of the expected need. At the launch of the Annual Report it was estimated that just 6 per cent of land bought from NAMA has been built on, prompting calls for a ‘use it or lose it tax’ to prevent land hoarding. The release of the report prompted ESRI’s Associate Research Professor Edgar Morgenroth to claim that Dublin had a dysfunctional housing market and government intervention was required.

Speaking on Newstalk with Construction Industry Federation (CIF) Director for Housing, Planning and Development Hubert Fitzpatrick. Edgar Morgenroth says: “House prices are rising at a significant rate at the present time. In normal circumstances this would encourage the building of greater house numbers. However, this is not happening in the Dublin area at the present time,” he says

The ESRI representative inferred that such circumstances could be brought about by developers sitting on land and waiting for prices to rise still further, adding: “By taking this approach, developers can seek to improve their profit margins on development land they already own.”

Morgenroth says that the introduction of a Developer’s Tax had been used successfully in other jurisdictions to prevent land from being artificially kept out of the housing market.

“There is no reason why such an approach cannot be replicated in Ireland. Land can be easily valued and assessed for tax purposes. The planning process will identify to what use land will be put. This could be single or multiple storey developments. Obviously, location will be a key factor in determining development land prices.”

Morgenroth hinted that an annual tax rate of between 3 per cent and 7 per cent would be punitive enough to encourage the building of more houses while, at the same time, not punishing developers unduly.

“The revenues lifted in this manner could then be used to fund social housing projects,” he says.

“But there remains a fundamental problem with regard to the working of the housing market in Dublin at the present time. It will take direct government intervention of some form to rectify this matter.”

Fitzpatrick made it clear that CIF does not condone the hoarding of land by developers.

“The opposite is, in fact, the case,” he says. “We are aware of the Government’s intention to look at the possible introduction of a Developers’ Tax in 2018. CIF members are in the business of building houses. This is how they earn a living. However, this is a very complex issue.

“In the first instance, there are significant areas of land that have been zoned for development that do not have the required services to allow their immediate development.

“It is highly significant that the €200 million Local Housing Activation Fund, introduced by the Government to facilitate the servicing of development sites, has been oversubscribed to a very large degree.

“This reflects the commitment of developers to get on with the building of the new houses that are required at the present time.”

Fitzpatrick says that it would be inherently unfair to levy a Developers’ Tax on locations that require considerable service works in order to get them ‘shovel-ready’. “Those sites that are building-ready should be developed immediately.”

Fitzpatrick queried the policy of NAMA to sell-off large parcels of development land, which could not be purchased by small to medium-sized construction companies in Ireland.

“This is another fundamental flaw in the way the Irish land market operates at the present time,” he says.

“Another issue that must be considered is that of developers paying exorbitant prices for sites and then having to wait for unit house prices to rise accordingly, prior to development taking place.”

Responding, Morgenroth says that NAMA is in a difficult position, when it comes to selling off land assets.

“The organisation was established to get the best valuable return for the State from the land and properties acquired after the economic crash,” he explains.

“The quicker these assets can be sold off at a viable price, the faster the State will claw back the outlays that were made in the first instance.”

The CIF Director admitted that NAMA should have built-in a development commitment clause when selling off land parcels to developers in the first place. He also claims that the government tax take from a new build house is far too high.

“Builders are currently paying VAT plus a host of other levies at the present time,” he says.

Actual building costs in the Republic of Ireland are on a par with those in the UK. However, it is the additional taxes and levies that act to increase relative costs.

“Up to 46 per cent of the costs incurred in building a new home are immediately diverted to Irish government coffers at the present time. VAT is levied at 13.5 per cent on new houses built in Ireland. The equivalent figure in the UK is zero.

“We also need to look at the issue of unit house size in Ireland. Compared with the UK, the current Irish figure is considerably larger. This is another factor that is feeding into the cost equation.”

Fitzpatrick adds: “There is an urgent need to get Irish building costs down. If this is not achieved, the only outcome will be an inexorable increase in the prices paid by home owners.”

Morgenroth points out that the Irish building sector had been the recipient of tax breaks, amounting to billions of euro in the past.

“Developers benefited to the tune of €10 billion in this regard between 2004 and 2014,” he says.

“There remains a fundamental problem with regard to the working of the housing market in Dublin at the present time. It will take direct government intervention of some form to rectify this matter.”

Morgenroth suggested a change in the tax laws to differentiate between the development of Green Field and Brown Field sites.

“The current Capital Gains Tax criteria should be re-assessed to reflect the more than significant increase in land values, once agricultural land is zoned for development.”

He also hinted that the associated increase in the government’s tax take could be used to fund new social housing schemes.

“The property market is strengthening at the present time, particularly in the greater Dublin area and house prices are set to rise further for the foreseeable future. This points to the growing demand for new houses, which developers are not meeting at the present time.

“There are a number of reasons for this, including high land prices, complex planning procedures and high construction costs.

“However, land hoarding on the part of construction companies, could well be a contributory factor and, in such instances, a relevant Developers’ Tax could be introduced by government.”