The Housing Supply Strategy for Northern Ireland

4th July 2022

The decarbonisation challenge: A UK perspective

4th July 2022Ireland’s housing conundrum

Ireland’s commendable humanitarian effort to house upwards of 200,000 Ukrainian refugees has starkly highlighted the very severe imbalances that still exist between supply and demand in the Irish housing market, writes Marie Hunt, Executive Director of CBRE Ireland.

While the current administration last year launched their ambitious 10-year Housing for All plan and are making progress with delivery of the various objectives within this comprehensive plan, the reality is that demand continues to significantly outstrip supply across all types and tenures of housing, a fact that has become even more apparent since discussions about housing refugees has come under the spotlight.

There are severe shortages of both public and private sector housing both for sale and to rent and the situation is particularly acute in major cities. Increasing supply of all types and tenures of housing is really the only answer to improving this situation. Encouragingly there has been a notable increase in building commencements over the last 12-month period but the construction sector will struggle to increase capacity to the sort of levels required to make a meaningful difference in the short term, particularly if the cost of construction continues to prove prohibitive.

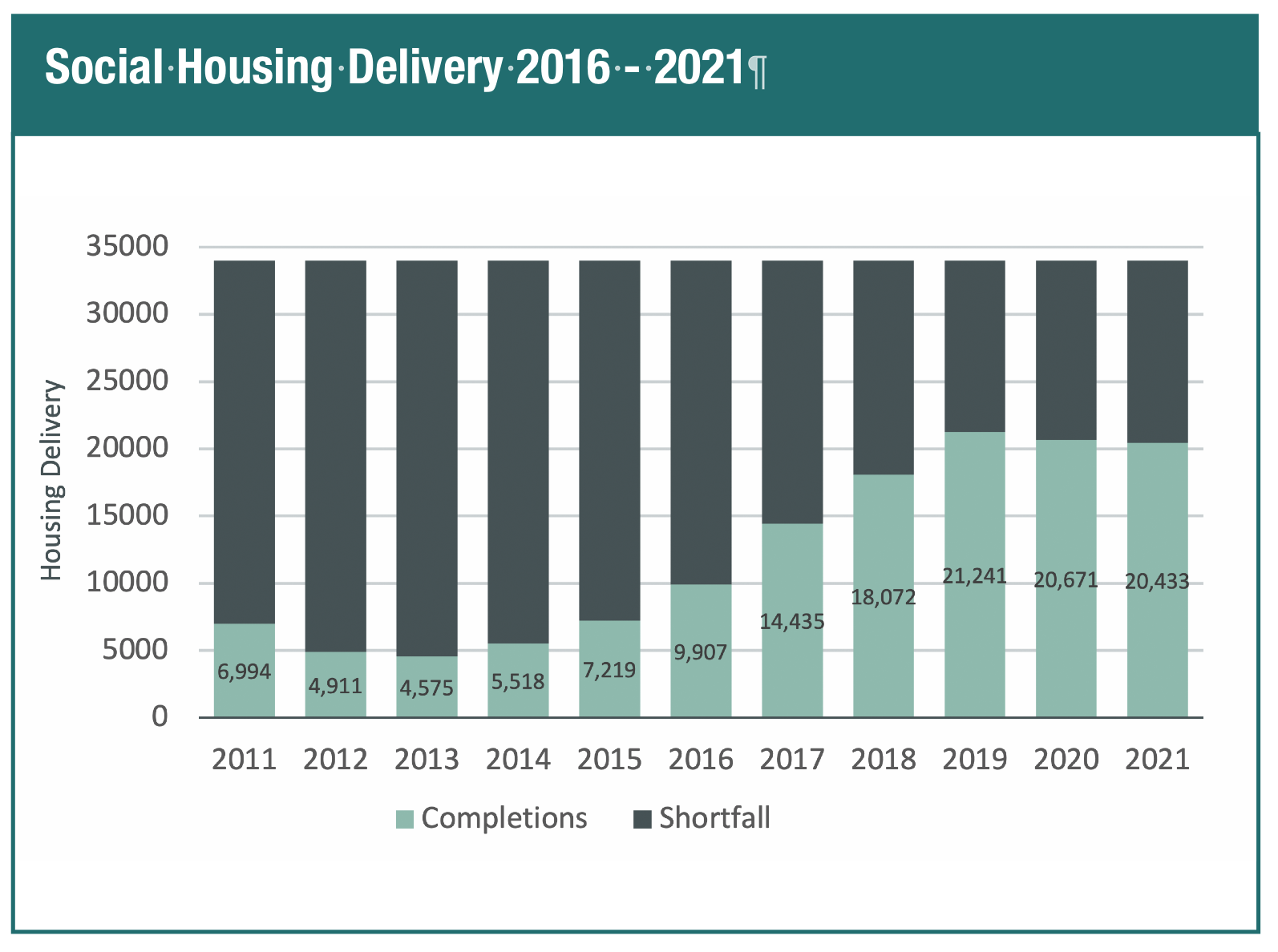

Under the Housing for All plan, the Government aims to deliver 34,000 housing units per annum, but we have consistently missed this target in each year of the last decade, stymied in 2020 and 2021 by the Covid-19 pandemic which stalled all but ‘essential’ construction. With build cost inflation now at extremely high levels and many housing schemes stalled in the lengthy planning process, the likelihood is that some schemes that were due for delivery in 2022, 2023 and 2024 may now be delayed, making it difficult to significantly exceed the delivery of 20,000 units per annum despite the best efforts of the construction industry. Importing additional labour to increase capacity in the construction sector isn’t the answer either considering that this migrant labour will also need to be housed.

While most focus is on the shortfall between the Government’s 34,000 annual target and the total volume of housing actually delivered each year, the starkness of the situation is particularly acute when considered cumulatively over a longer time horizon. In fact, the cumulative shortfall of houses not delivered since 2011 is now over 240,000 housing units, which would go a long way towards meeting the needs of the those looking to secure mortgages and purchase homes or in addressing the exceptionally high social housing lists within every local authority in the country.

Although there are more than 60,000 households on social housing waiting lists, of which approximately 14,000 are in the Dublin region, only 5,142 new build social homes were delivered in the entire country in 2021, which is disappointing considering that the target was 9,500. Although government aspires to a situation where the bulk of new housing is delivered by the public sector, only approximately 20 per cent of the social homes delivered last year were provided by local authorities or approved housing bodies. This clearly points to the need to come up with a sensible solution to reduce bureaucracy and empower these bodies to increase delivery as well as coming up with a solution to facilitate long-term leasing in some form and capitalise on the strong investor demand to deploy capital into social housing delivery.

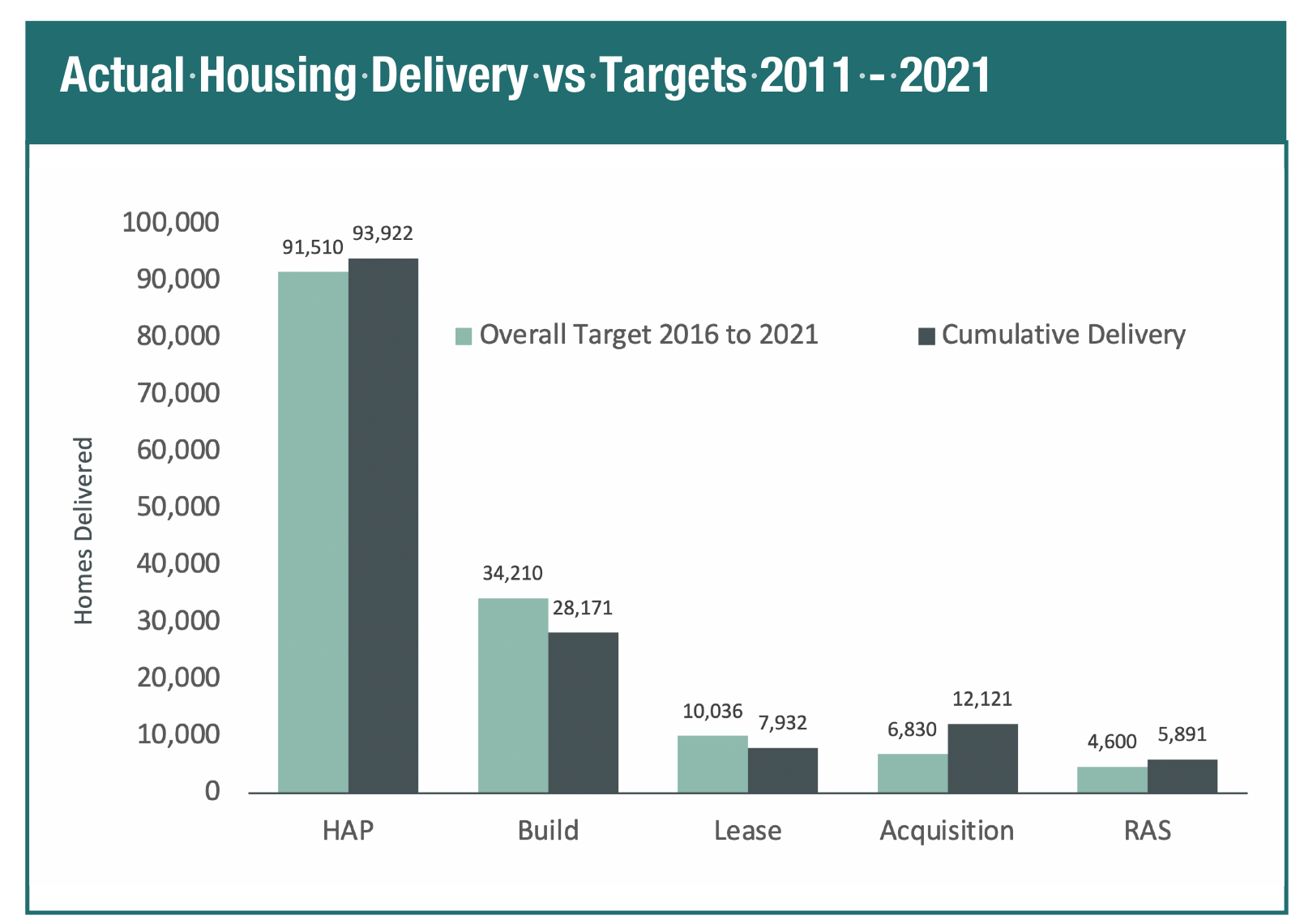

In total, more than 148,000 social housing applicants were removed from local authority housing lists in the Irish market between 2016 and 2021, which is commendable. However, more than 63 per cent of this was achieved by moving applicant onto the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) scheme with less than 20 per cent emanating from the development of new housing by local authorities or approved housing bodies. Only 5 per cent were accommodated by way of local authorities or approved housing bodies entering long-term leases with investors despite strong demand from investors to deliver accommodation under this mechanism. While many dislike this form of delivery on the basis that the asset doesn’t revert to the State at the end of the term of the lease, surely this particular aspect of the current regime could be revisited to devise a mechanism that delivers for both the State and the investor?

Developers are currently making genuine efforts to ramp up housing delivery by a variety of means but it is unrealistic to believe that we can reach output of 34,000 units per annum whilst simultaneously addressing the backlog of the last decade, rolling out a national retrofit programme and remedying all of the Mica-affected homes on the west coast without collaboration between both the public and private sector and without the assistance of overseas capital. Increasing HAP payments will do little to alleviate the critical issue which is a lack of supply of housing units.

It is clear that a number of other measures in addition to increasing the delivery of new accommodation will be required to increase supply including the timely adaptation of vacant and underutilised properties across the State. Recent analysis undertaken by ULI Ireland on Adaptive Reuse succinctly identified the plethora of issues hindering adaption and utilisation of the thousands of vacant buildings across the State and has set out clear recommendations on how these obstacles might be overcome.

The arrival of Ukrainian refugees to Ireland over recent months has refocused minds. We need to use this as an opportunity to look for meaningful solutions that can be implemented quickly and leave no stone unturned to address Ireland’s housing conundrum for once and for all.

E: marie.hunt@cbre.com

W: www.cbre.com